by Mikhaeyla Kopievsky

As some of you may know, I am on the home stretch of finishing the first draft of a contemporary fantasy novel that I’ve been writing on-and-off since 2021. For the last six months, I’ve finally been able to dedicate some serious writing time to it (having finished two other novels that were in development/editing). Which would have been great, but I was stuck. Worse, I was stuck at the beginning of the third act, when story momentum was supposed to be rushing me to the end.

(For those of you who are new to story structure and, in particular, the three and four act structure, check out my earlier posts).

For those of you who have been following the blog for a while, you might remember that I once wrote about how the third act is one of my favourites to write – that, like the first act, it is full of energy, mostly because the momentum from the rest of the story is pushing it to its natural resolution. But, here I was with this current wip, at the beginning of the final act, launching into the epic final battle, and…nothing. I had hit a serious go-slow.

Something was clearly wrong.

(Image courtesy of Md Meraz via Unsplash)

The Problem

At first I thought it was a problem with the beat just before Act 3 launches – the ‘Dark Night of the Soul’. This beat is explored in Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat and there are hundreds of online articles and videos about it. It’s often called the ‘All is Lost’ moment – the moment when, after the protagonist’s false victory, everything comes crashing down and the hero loses what they most hold dear.

In my story, the Dark Night/All is Lost moment was the beginning of a major assault by the enemy. But, after I started writing it, it didn’t feel right. It wasn’t personal enough. So I escalated it further and put the protagonist and her friends in peril, but it still didn’t feel right. There wasn’t any real emotional resonance – it was all action and universal stakes (we could lose our lives) rather than personal stakes (something specific and unique to the main character).

So I escalated again, this time having the hero and her friends in more isolated and targeted danger, and having her faced with the choice between loyalty and duty.

And this I was happy with. The only problem? It was occurring way too late in what was still felt like the third act.

This presented a whole range of problems –

- The act ratios (in terms of relative length) were way out – Act 1 and 2A were reasonably balanced. Act 2B was way too long. And Act 3, which didn’t have the clear delineation it needed with Act 2B, felt tiny.

- I couldn’t bring the ‘more isolated and targeted danger’ scene earlier – it would have felt rushed and unearned, but I also couldn’t leave it where it was. As the Dark Night/All is Lost moment, it was supposed to signal the beginning of the third act, but I already felt I was waist-deep in it.

And, being the writer I am, I was unable to give up on this niggling doubt and just keep writing. I needed to figure out where I had gone wrong (because, as I’d discovered when writing my first novel, the problem is usually found earlier in the story).

Story Structure Analysis

My way of figuring out where something has messed up is to pull the whole thing apart. In this case, it meant going back and doing some detailed scene, chapter, and act analysis. There are lots of ways to do this analysis and I’ve tried a few different methods and their variations over the past few years (Story Grid and Save the Cat are particularly useful), but this time I tried to riff off Dwight Swain’s idea of ‘scenes’ and ‘sequels’ – where:

- SCENES comprise a Goal (wanting or needing something), Conflict (opposition to getting that something), and Disaster (negative outcome from the opposition that puts the protagonist in a worse place (stakes are raised, strengths are weakened, additional constraints are added, etc, etc), and

- SEQUELS (the scenes/chapter that follows) comprise a Reaction (how the hero responds to the setback), Dilemma (a less than ideal choice the hero has to make), and Decision (which then creates a new goal and sets off the whole sequence again).

It’s a pretty tidy structure – part of the reason it is so appealing to writers – but I couldn’t make it gel with my story. It was too linear: in my story, I have goals that lead to conflict, that lead to additional conflict, that lead to dilemmas that lead to reactions that lead to more conflict, etc, etc (you get the point). It was also too narrow: terms like ‘conflict’, ‘disaster’, ‘dilemma’ (and even ‘goal’) seemed too one-dimensional and didn’t allow for softer versions – like ‘tension’, ‘complication’ or ‘intrigue’, or ‘trajectory’, ‘set-back’ or ‘detour’.

My 5 Part “Story Momentum Model”

So, I came up with my own way of analysing the story, still using that similar, causal Motivation-Reaction sequence, but instead comprising five key aspects:

- Trajectory: this is the thing that is giving the protagonist velocity – direction and urgency. It can be a goal, but it can also be a desire, or even just a destination. You might think they all look like they mean the same thing 🙂 But to me, the subtle differences are meaningful. It’s easier for me to say (and feel that it is true) that my protagonist desires X, without saying that my protagonist necessarily has the goal to actively obtain X.

. - Complication: this is the thing that obstructs the protagonist’s trajectory, by changing its direction or speed. It can be an obstacle (something standing in opposition) or it can be an encounter (something coming from a different direction). Sometimes these obstacles and encounters can slow or speed the protagonist along their original trajectory, sometimes they can set them on an amended or altogether-new trajectory.

. - Escalation: this is the value the complication represents. Either an obstacle or encounter will generate intrigue, tension, or conflict. The escalation has to have an additive quality – it can’t represent much of the same; something has to be heightened.

. - Response: this is what the protagonist does in the face of the complication and its escalation. The protagonist can engage in the conflict, or they can avoid it and set off on a detour. They can escalate the tension, or they can live with it (and continue on their original path), or they can reconcile it. They can ignore the intrigue (and continue on their original path) or they can explore it. The response is what drives whether the plot continues on its original trajectory (with added/growing complications or deepening of character arc) or diverts along a new one.

5. Result: this is the outcome of the character’s response (no good deed goes unpunished) and the options are more extensive and varied. The result will either set them up with a new Trajectory, present a new Complication, generate Escalation, or lead to one of these plot developments:

- Discovery: where new resources, assets, information or understanding is uncovered

- Deepening: where either character development progresses (they get closer to being the person they need to become (or, in a tragedy, get further away), or character relationships progress from superficial to authentic (or, in a tragedy get worse/more toxic).

- Pain/Loss: where the character faces a set-back, loses something of importance, is injured or experiences pain, etc. This isn’t a total disaster, but a weakening of the character. Often occurs after the protagonist wins or succeeds in something – the “yes, but” approach to maintaining and developing story tension (nothing of value comes cheaply).

- Disaster: where the character is left in a position worse than where they were before their response. Often occurs after the protagonist is defeated – the “no, and” approach to maintaining and developing story tension (twisting the knife deeper/adding salt to the wound).

- Resolution: where the obstacle or escalation is resolved (allowing for the next obstacle or escalation to gain dominance). This is an important part of story momentum – giving the protagonist wins, so that they can advance to the next phase.

Applying the Model

Now that I had a model that made sense to me, I could go back and apply it to my story. To do that, I started an Excel sheet that set up the rows with:

- the scene number

- a brief summary of its events

and then against each scene (i.e. in the spreadsheet columns), articulated:

- the number of pages/wordcount

- the story day and time it occurred (this was super general, e.g. A1, Mid Morning (where A1 represented Day 1 in this particular sequence))

- the characters involved

- its ‘energy’ level on a scale of 1-5 (where 1 was little or no drama and 5 was maximum dramatic conflict and action)

- whether it introduced a Trajectory, Complication, Escalation, Response, and/or Result

- what type was introduced (e.g. “Trajectory: Desire, Complication: Tension”)

Even though this worked out really well in Excel, you could just as easily use colour-coded post-its if you’re working with printed sheets of paper, or colour coding, keywords, and notes in Scrivener (I like the idea of colour coding for energy levels and using the keywords to identify what aspects of the Story Momentum Model are being introduced, and notes to flesh out what the types are).

Does it Work?

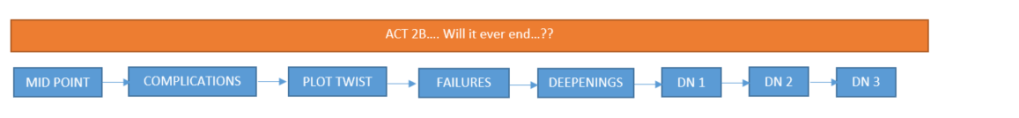

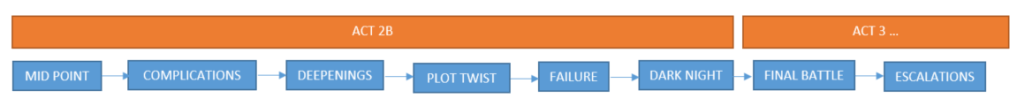

It definitely did for me! Not only did I uncover my ‘Albuquerque’ moment, I also identified other plot holes and opportunities for tightening my plot. I realised, from both the Story Momentum Model and the scene energy analysis, that key events in Act 2B were out of order – that, essentially, I’d revealed the plot twist too early and introduced the ‘Deepening’ elements too late. By re-arranging them, I was able to use the Deepening moments to build the tension up to the twist, which I could then use as my true Dark Night/All is Lost Moment.

It looks pretty simple when you see it laid out like it is above, but it’s important to remember that until I did the scene analysis, I didn’t know what my complications, deepenings, and failures were. They were just story beats in random scenes. I needed to dig into them to figure out what they represented at the plot level, and from there I could see that I had mixed up their order. (The scene energy analysis was also super helpful in seeing where the momentum was de-escalating instead of escalating, which also helped to get the order right (as George Saunders is often fond of saying, always be escalating)).

Does it work for all kinds of stories?

I don’t see why not… I think it’s probably going to be more useful for quieter, non-linear, more complex stories, but there’s nothing to suggest it can’t be used for louder, faster-paced, action-driven stories. I think in terms of the latter, there just won’t be much additional benefit beyond Swain’s ‘Scenes and Sequels’ approach.

But, for added reassurance, in the next post, I’ll apply the model to a novel or movie to demonstrate it in action 🙂

And if you use my Story Momentum Model to analyse your own novel, please let me know in the comments!

Discover more from Mikhaeyla Kopievsky

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “The Dreaded Slow-Down: When story momentum fails you”