by Mikhaeyla Kopievsky

Over the last couple of weeks I have been looking at story structure – from the global level of the story itself, to the macro level of each act within the story. This week, I am looking at story structure at the micro level – Sequences, Scenes and Beats.

Before we move on into the discussion, let’s do a quick recap:

1. The novel is like a Russian Doll – the biggest doll (our novel) contains smaller replicas of itself within itself. The content won’t necessarily replicate in miniature, but the structure will (as will, to different degrees, the tone and theme).

2. The structure is many things to many people – countless authors and writing gurus have all attempted to distil structure into the key building blocks (Snyder’s Save the Cat, Aristotle’s Three Act Structure, Bell’s LOCK and Two Doorways, Coyne’s Story Grid, Brooks’ Four Boxes) – but sometimes you just have to build something that works for you.

My structural breakdown goes like this:

1. Status Quo

2. Call to Action

3. Engagement

4. Crisis Point

5. Directed Action

6. Outcome

So far we have seen this model present across the entire novel and across each of the three acts that a novel comprises.

Today, let’s see how the model presents in the micro components of a novel – sequences, scenes and beats.

Sequences, Scenes and Beats

Sequences, scenes and beats are possibly the hardest parts of structure to bed down – primarily because there are lots of definitions out there on what each of them is, but also because they are more directly associated with films rather than novels.

Let’s look at each in turn…

Sequences

Sequences are the next doll to come out of the shell – the miniature replica of the act.

I find that Wikipedia has the best definition:

In film, a sequence is a series of scenes that form a distinct narrative unit, which is usually connected either by unity of location or unity of time.

When I first started planning my debut novel, Divided Elements – Resistance, I found that my outlining process consisted entirely of acts and sequences. Sequences are the large chunks of story that give structure to the acts. They’re also likely to be the structural elements people use to summarise your story.

This happens to me all the time – I’ll be talking to someone about a movie I saw on the weekend and the first question they will ask is “What was it about?”

“Well,” I’ll say. “It was this sci-fi movie called Snowpiercer, where there is this train hurtling through the snow and ice, and people are divided into classes and designated to different carriages, and there’s a plot afoot to get to the engine and basically start a revolution – you know, power to the people.”

And then, if they’re not particularly interested in seeing the film, but still a little intrigued, they will ask “What happens?”. And this is where I launch into the rundown of sequences:

“Well! The plebs in the back carriage are receiving revolutionary messages and intel in the soylent green like food bars they get dished up and so they stage a revolt to find the one person who can get them to the engine room. They make it to the jail carriage where they release the drug-addled mastermind that can get them through the next few carriages and all the way to the engine room – He gets them to the the next carriage but it is filled with murderous guards with some serious technology and killer weapons, leading the charge is the creepy Prime Minister of the train. She gets captured and forced into helping them get to the front on pain of death…” etc etc

It’s the Cliff Notes version of the story – just enough detail to get a sense of the story and how it unfolds, but not enough detail to get a sense of the world complexities or character motivations and development. In this way, sequences tend to be action-driven – they detail what is happening – the physical/tangible triggers for story and character development.

The sequences focus on what happens, leaving it to the scenes to answer the more difficult questions of why and how, to explore the more complex story elements of worldbuilding, character development, inner turmoil and tension.

But like their own mama doll, sequences still follow the same structure of status quo, call to action, engagement, crisis point, directed action and outcome.

Let’s take the Snowpiercer example – Sequence 1 would be the “Stage revolt and get to jail carriage”.

The status quo details the conditions of the last carriage and the frustration and fears of its occupants. The call to action is the latest message found in the food bar – it’s time to start this revolution. The engagement is the fight with the guards. The crisis point is where the protagonist is confronted with a gun-bearing guard and he has to decide whether to trust the intel (that the guns aren’t loaded) or back down. The directed action is where he back the intel and his instincts and doesn’t back down. He leads the surge through to the next carriage. The outcome is arriving at the jail carriage and the cell of the key person they are after.

Scenes

Scenes are the next doll to emerge. If I could establish a definition for them, I would use something very similar to that of sequences:

A scenes is a collection of beats that form a distinct event, which usually takes place within one location or one time period.

Think of them like the building blocks you need to achieve the overarching premise of your sequence. The protagonist and his friends need to successfully stage a revolt and make it to the jail carriage. What ingredients are needed to make this cake rise? Well, we will need a scene that shows a kind of ‘tipping point’ of frustration amongst the occupants of the carriage and the introduction of a ‘safe breaker’ – something that will enable them to vent their frustrations. That’s our scene: “Just as the tension is about to turn critical, they receive a secret message that gives them the key to success”.

Like a sequence, it also gets fleshed out with the structural elements. The status quo is the tension. The call to action is the realisation that the tension will hit the tipping point soon and potentially cause a lot of grief – something needs to be done. The engagement is the futile attempts to calm everyone down. The crisis point is when the protagonist considers starting the revolt without knowing it is the right time. The directed action is the protagonist waiting – tense, yet patiently – to receive word before he acts. The outcome is the protagonist being rewarded with the secret message that tells him the time is right.

Beats

Beats are tricky things. I am wary of approaching them – they seem as if they exist on Planck Scale, where things don’t play according to the normal rules.

Like most of the other dolls that have gone before them, beats are indeed a miniature replica. Unlike the other dolls, they have no additional, smaller doll within them. They are the last component. As such, beats themselves are not further divided into smaller parts – they are the smaller parts.

Film-makers like to break down their scenes into two components – the beat and the shot. Both are like twin atoms – equally representing the smallest unit of the story. The beat refers to the narrative unit, the shot to the visual unit. Both explain what is happening – they literally tell the story.

Let’s use an example: Let’s say that in this paticular scene in your story you want to write about a teenager named Izzy switching on the memory-erasing machine.

Okay, let’s start with the ‘beat’. From what I can understand, there a few types of ‘beats’ – the most common being action beats, dialogue beats and internalisation beats. There are also, from my observation, explanation/exposition beats, description beats and flash-back beats:

The time machine stood gleaming like a metal meerkat, perched on tippy-toes, standing as straight as could be in anticipation of the excitement or danger that could come next [description]. Izzy crept forward, her grin growing wider with each step [action]. “Eliana would be flipping out…”, she whispered to hersel [dialogue]. The thought of her best friend, Eliana – former best friend [internalisation] – draws Izzy up short. Her grin wavers as she recalls their last conversation. Ten years as best friends had fizzled in a space of ten minutes .

“You are so selfish!” Eliana had raged.

“I’m not selfish,” Izzy had retorted. “You’re scared!” [flash-back]

Okay, so the above example is a little convoluted – courtesy of trying to fit in all the beat types – but you see the point. There are a lot of beat types and each presents an interesting way of conveying information.

Now, let’s turn to the less popular ‘shot’.

Again, Wikipedia brings the goods with a useful description:

[A] shot is a series of frames, that runs for an uninterrupted period of time. Film shots are an essential aspect of a movie where angles, transition and cuts are used to further express emotion, ideas and movement.

Film shots are typically defined by three criteria – Subject (who or what is predominantly captured); Field Size (how much of the subject and its surrounding environment is captured); and Camera Placement (from what angle or perspective the image is being captured).

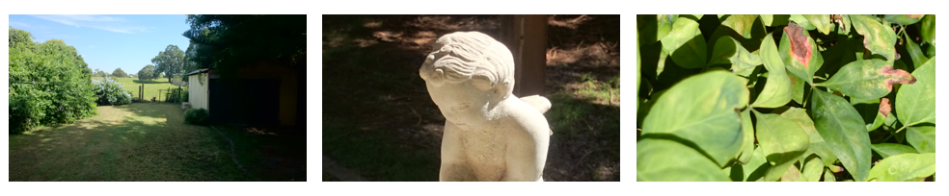

Compare the following:

Subject: > Backyard > Fountain > Foliage

Field Size: Wide Shot > Mid Shot > Close Up

Camera Placement: Aerial > Profile > Behind

Even though, as authors, we are dealing with the narrative (and not the visual) – we can still take some lessons away:

The true importance of beats lies not with them, in and of themselves – but with the juxtaposition of, and transition between, them.

Positioning a wide-shot beat (where we see the chaotic movement of a crowd, which includes the protagonist) next to a close-up beat (where we see in full detail the protagonist’s smile) – conveys a very precise tone and emotion. Without any explanation necessary, we know instinctively that the protagonist is smiling either because she likes the chaos or feels responsible for it.

Positioned deep within the large crowd of frenetic bodies, Jane whirled her limbs in a frenzy, mimicing and leading the replicated chaos around her. Shouts and smells assaulted her senses as she jostled, and was jostled back.

She smiled.

This tone can be sharpened by using a cut-away shot – i.e. juxtaposing a ‘shot’ of the crowd in chaos, with the protagonist nowhere to be seen, and then cutting sharply to a close-up of the protagonist’s smile.

The crowd was an angry mass of frenetic limbs. People of all shapes and sizes jostled and heaved. From the balconies above it appeared as if the large gathering was boiling, bubbling desperately and breaking into large pockets of isolated and connected violence.

Away from the crowd, on the isolated street corner, Jane watched on. Her eyes never wavered from the chaos – taking in every movement, every assault, every climbing degree of violence.

Alone and unwatched, she smiled.

Each beat conveys a very specific tone and emotion. In the first example, seeing Jane in the midst of the chaos from the very beginning, gives us a very different feel to the second example, where we don’t know of Jane yet and don’t know where she is. Finding her alone and isolated from the chaos provides a darker tone. And, even though both examples end with her smiling – one feels more sinister than the other.

Both seem to also serve different purposes for the scene. The first is more likely to be an Engagement beat – it speaks of fun & games. The second appears to be a Directed Action beat – there is something decidedly conscious and calculating about this smile.

Within any given scene, there will be multiple and various beats – some will be status quo beats, some will be call to action beats. You could have multiple call to action beats, all ‘shot’ from different lengths and perspectives and juxtaposed to create the overall mood you are aiming for, and just one outcome beat – a final ‘fullstop’ at the end of the scene.

In that way, beats live up to their musical etymology – stringing together short beats and long beats, loud beats and soft beats, slow beats and fast beats – it’s what gives you the narrative music 🙂

So, there you have it – the final look at Story Structure from a micro perspective. I hope you have found it useful!

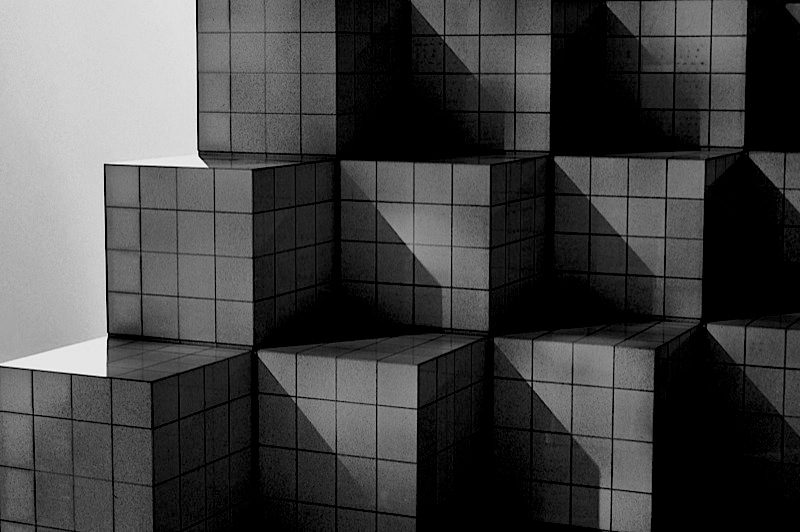

(Featured Image derived from “365/173: Building Blocks” courtesy of Kaytee Riek via Flickr Creative Commons)

Thank you, that is very useful indeed. I think the concept of beat is the most difficult to comprehend but I love the comparison with musical beats and the concept of “narrative music” that makes the plot flow and beat like a heart. In fact comparing it with music made it less amorphous and abstract and stopped me from looking at it as a concrete and unchangeable structural element that becomes a hindrance.

I also realise that I belong to those writers where I have to look at structure after I have finished the first draft as trying to forcefully fit chaotic thoughts and plot unravelling in a predefined structure has led me to severe blocking in the past and untold frustration. Looking at the first draft with the intent of analysing it much like you analysed the structure in your series of posts will help me organise the revision and re-vision of the story in terms of structure and visualise the flowing of the plot.

I’m so grateful for you posting these series, thank you so very much.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome! Yes, ‘beats’ are the trickiest to understand – and everyone seems to have their own unique take on them. I like the idea of focusing more on the their volume, density, juxtaposition and transition as a way of conveying tone and emotion – will definitely use that in my own revision process!

LikeLiked by 1 person